From 2016 until 2019, Random Institute ran the curatorial program of the international contemporary art center Despacio in San José, Costa Rica.

This site was coded by Sarvesh Dwivedi and Emmanouil Zoumpoulakis and designed by Sandino Scheidegger.

Beauty in the Dark

The places we yearn to be are as different as we who long for them. Faraway places created by lonely fantasies and experiences of anxiety. Like the horizon, our yearnings move with us, disappearing and then reemerging once again. They are spiritual resting places that permit us to dream what we will presumably never see—just as we will never see what is concealed beyond the final horizon because we will never cross it.

Essay about Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa.

ThoughtsThoughts

Read the essay in German: Die Schönheit im Dunkeln (below)

Beauty in the Dark

The places we yearn to be are as different as we who long for them. Faraway places created by lonely fantasies and experiences of anxiety. Like the horizon, our yearnings move with us, disappearing and then reemerging once again. They are spiritual resting places that permit us to dream what we will presumably never see—just as we will never see what is concealed beyond the final horizon because we will never cross it.

Yearning is common to all of us but can nonetheless scarcely be grasped. Those looking for longing can find it revealed at the wellsprings of art, literature, and the beautiful. In the arts it becomes possible to enter into and experience imagined worlds, and in some cases they even become the pilgrimage sites of a collective longing.

Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa’s oeuvre is one of these longed-for places. The artist, born in Guatemala in 1978, uses his poetic performances and installations to set free emotions that move us. Viewers become fellow travelers, and Ramírez-Figueroa draws them into a fanciful spiritual landscape. In doing so, he repeatedly alludes to his native country. While a homeland represents a harmonious organic situation in life, for Ramírez-Figueroa the narrative model never occurred in that form.

Before we turn to the works of his solo exhibition Two Flamingos Copulating on a Tin Roof at the Museum Haus Esters in Krefeld, it makes sense to briefly trace the path of the artist’s moving biography. It is precisely in the inner dialectic between work and life that we find the special qualities that make his art unique. Like almost no other artist, Ramírez-Figueroa uses extremely intimate works to open up a universal scope and to point to a path leading far beyond art.

Ramírez-Figueroa was born at the halfway point of the Guatemalan civil war. In 1978 the war had already been raging for 18 years. No one had any idea that the same amount of time would have to pass again before peace would be established. Over 200,000 people fell victim to the fighting between the military dictatorships and the guerrillas. Few people remained unscathed, and the artist’s family was no exception. Those who are born into times of war and are unfamiliar with any peace to serve as a point of reference are able to endure a lot—to a certain extent, even the realities of a civil war. However, with the execution of Ramírez-Figueroa’s uncle, things reached an unbearable point. His grandmother set out to flee to the north with the boy, who was only eight.

They left behind the only reality they knew and a family that the war would tear apart more and more until they finally stood divided against one another and engaged in acts that no one wants to read about here, not to mention personally experience.

Stranded as a political refugee in Vancouver, a new life began. This city on the west coast of Canada became a place of retreat, where he could work through his experiences. The pain of leaving was balanced by the joy of arriving. Ramírez-Figueroa’s youth awaited him—that unavoidable waiting area between dreamy play and dutiful action. Responsibility came sooner than expected, with his grandmother becoming severely ill and requiring daily care. As an adolescent, Ramírez-Figueroa accepted responsibility for her care. And with his dying grandmother, his feeling of a homeland in exile also departed.

Surprisingly, the artist conceals the dramatic coordinates of his own life; throughout Two Flamingos Copulating on a Tin Roof, they are at most suggested.

Fettered Flamingos, 2017

The path of anyone entering the exhibition is first blocked by five bound flamingos (Fettered Flamingos). The fragile bipeds, formed out of Styrofoam and covered in pink enamel, twist around as though they want to free themselves from the chains lying around them and flee. Those who look closely will not fail to notice that the slightly deformed creatures look as though they had long since lost their minds. The attempt to set out for new lagoons seems hopeless. Their house arrest has metamorphosed into a new normality—as though they had arranged themselves with and resigned themselves to the reality of their lives.

Liquid Coral, 2017

Folding partitions stand in a second room, arranged in a circle to protect their interior from view. They subliminally recall a station for medical care and initially conceal more than they reveal. A gap in the row of partitions lures to the inside, where one finds a delicately constructed bloodletting chair. On its armrest is a red glass sculpture in the form of an oversized blood vessel and reminiscent of a piece of coral, corresponding to the work’s name: Liquid Coral. The fragility of the tubular structure has a decelerating effect: In order to take everything in, one must reverently creep in a circle around the chair and the blown-glass sculpture. This generates an intimacy that is overwhelmingly omnipresent—all the more so because the antiquated notion of bloodletting for healing ailments of any kind seems bizarre today and was nonetheless practiced for centuries. This glass sculpture is made of extremely rare, melted-down, red church-window glass, which originally served to divide inside from outside and the worldly from the otherworldly.

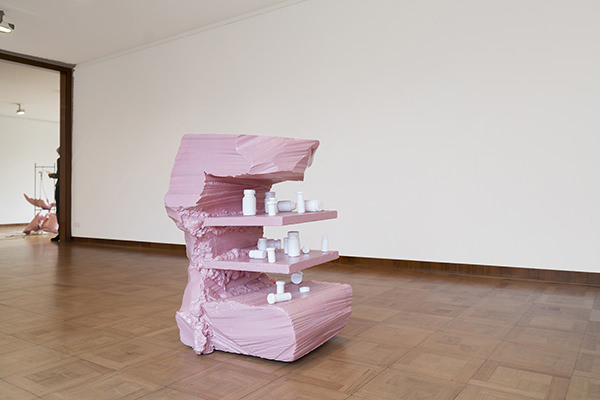

Shelf with Medicine Bottles, 2017

An additional room reveals a peculiar medicine cabinet formed out of roughly worked pink Styrofoam and filled with abstract versions of white containers for storing medicine. The work, Shelf with Medicine Bottles, calls to mind a nervous yearning to be “healed” or the wish to delay what comes at the end of life. The arrangement of the medicine bottles suggests that someone was searching for a cure in a hurry and carelessly rifled through the cabinet. Life as an eternal health-care situation is not anyone’s aspiration, but it is more and more frequently becoming a reality. Consider continuous efforts to keep the constantly aging human body alive as long as possible. Ramírez-Figueroa assures me that suffering also means feeling alive and points to the narrative staging of the foot stepping out of the medicine cabinet.

The installation speaks to the world through an honest sensibility that depicts what people persistently try to ignore with an optimism based on the progress of technology and medicine: that people, as living creatures, are subject to the morbidly gnawing conditions of time—regardless of all the yearning.

Comb Bound Sound, 2017

A further room once again contains an intimate, almost stage-like arrangement of partitions—this time with the fabric dyed blue. In the center is a Venus comb murex (Murex pecten), an extremely fragile sea creature that the artist has had produced from transparent glass. It is modeled on the illustrative watercolor drawings that very often stand at the beginning of his creative process. The work is titled Comb Bound Sound. The dampened sound of music emerges out of the rock snail’s insides. Listen closely and recognize a fandango melody, which causes the spiny shell to vibrate slightly. Fandango is a Spanish-sung dance whose name can be traced etymologically to fandanguero, a word for slaves who secretly performed dances and supposedly brought about a nocturnal tumult. Ramírez-Figueroa has chosen an interpretation by the U.S. harpsichordist Scott Ross, who passed away at far too young an age from complications caused by AIDS and kept his own yearnings and desires concealed, with the result that many of them never clearly resonated through to the outside world.

Every one of Ramírez-Figueroa’s works digs down to unearth deeper geological strata of life and then pauses there. The fact that someone is talking about himself and his life here—without uttering a single word about them—can also be recognized in the exhibition.

His fleeting dream worlds show us where we expect to find beauty but don’t see it. In searching for this beauty, we are rewarded with the feeling that we have found it—as though we were standing opposite beauty for a brief moment within the darkness. Surrounded by the memories and fantasies of one of contemporary art’s most unconventional artists, he teaches us—like no other—that we do not have to see beauty to know that it is indestructible.

Die Schönheit im Dunkeln

Sehnsuchtsorte sind so verschieden wie die Menschen, die sie herbeisehnen. Ferne Orte; erschaffen aus einsamen Fantasien und gelebten Sorgen. Wie der Horizont bewegen sich unsere Sehnsüchte mit uns, um im Nebel des Lebens zu entschwinden und abermals aufzutauchen. Es sind geistige Ruhestätten, die uns erträumen lassen, was wir wohl nie sehen werden. Genauso wenig wie das, was sich hinter dem letzten Horizont verbirgt, weil wir den nie passieren werden.

Die Sehnsucht ist uns allen gemein und dennoch kaum fassbar. Wer die Sehnsucht sucht, der findet sie freigelegt an der Quelle der Kunst, der Literatur und des Schönen. In den Künsten werden erträumte Welten zugänglich, erlebbar und in manchen Fällen gar zu Pilgerstätten kollektiver Sehnsucht.

Naufus Ramírez-Figueroas Œuvre ist einer dieser Sehnsuchtsorte. Der 1978 in Guatemala geborene Künstler setzt mit seinen poetischen Performances und installativen Werken Emotionen frei, die uns berühren. Betrachter werden zu Mitreisenden, die Ramírez-Figueroa in eine fantasievolle Seelenlandschaft lockt. Dabei verweist er immer wieder auf sein Heimatland. Während Heimat für gewachsene Lebensverhältnisse steht, ist sie für Ramírez-Figueroa ein narrativer Lebensentwurf, der so nie stattgefunden hat.

Bevor wir auf die Werke seiner Einzelausstellung Die Vereinigung zweier Flamingos auf einem Blechdach im Museum Haus Esters in Krefeld zu sprechen kommen, bietet es sich an, einen Streifzug durch die bewegte und bewegende Biografie des Künstlers zu machen. Denn gerade in der innigen Dialektik zwischen Werk und Leben finden sich Besonderheiten, die seine Kunst einzigartig machen. Wie fast kein anderer Künstler schafft Ramírez-Figueroa mit höchst intimen Werken eine universelle Reichweite und weist den Weg über die Kunst hinaus.

Ramírez-Figueroa ist in der Halbzeit des guatemaltekischen Bürgerkriegs geboren. Im Jahr 1978 wütete der Krieg bereits 18 Jahre. Damals ahnte niemand, dass noch einmal genauso viel Zeit vergehen musste, bis sich der Frieden durchsetzte. Den Kämpfen zwischen den Militärdiktaturen und den Guerillas fielen über 200’000 Menschen zum Opfer. Verschont wurden wenige – auch nicht die Familie des Künstlers. Wer in kriegerische Zeiten hineingeboren wird und den Frieden nicht als Referenz kennt, erträgt vieles – bis zu einem gewissen Grad sogar die Realitäten eines Bürgerkriegs. Mit der Exekution von Ramírez-Figueroas Onkel war jedoch die Unerträglichkeit erreicht. Seine Großmutter setzte mit dem erst Achtjährigen zur Flucht in den Norden an.

Zurück ließen sie die einzige Realität, die sie kannten, und eine Familie, die durch den Krieg immer mehr auseinandergerissen wurde, sich letztlich entzweit gegenüberstand und zu Taten schritt, welche man hier nicht lesen, geschweige denn selbst erleben möchte.

Als politischer Flüchtling gestrandet in Vancouver fing ein neues Leben an. Die Stadt an der Westküste Kanadas wurde zum Rückzugsort, um Erlebtes zu verarbeiten. Der Schmerz des Weggehens wurde aufgewogen durch die Freude des Ankommens. Es wartete die Jugend auf Ramírez-Figueroa, der unvermeidliche Wartesaal zwischen träumerischem Spiel und verantwortungsvollem Handeln. Die Verantwortung kam früher als erwartet, weil die Großmutter schwer erkrankte und auf tägliche Pflege angewiesen war. Als Heranwachsender nahm sich Ramírez-Figueroa der Betreuungspflicht an, und mit der sterbenden Großmutter verabschiedete sich im Exil auch das Gefühl von Heimat.

So viel zur Vorgeschichte. Anders als zu erwarten, unterschlägt der Künstler die dramatischen Koordinaten der eigenen Lebensstationen, die sich in der Ausstellung Die Vereinigung zweier Flamingos auf einem Blechdach höchstens andeuten, aber nie aufdrängen.

Gefesselte Flamingos, 2017

Wer die Ausstellung betritt, dem stellen sich erst einmal fünf angekettete Flamingos in den Weg (Gefesselte Flamingos). Die fragilen Zweifüßer – geformt aus Styropor und umhüllt mit rosa Lack – verrenken sich, als möchten sie sich aus den herumliegenden Ketten lösen und zur Flucht ansetzen. Wer genau hinsieht, dem entgeht nicht, dass die leicht deformierten Wesen aussehen, als hätten sie längst den Verstand verloren. Der Versuch, zu neuen Deichen aufzubrechen, scheint aussichtslos. Der häusliche Arrest wandelt sich zur neuen Normalität – als ob sie sich mit der Lebensrealität arrangiert und abgefunden hätten.

Flüssigkoralle, 2017

In einem zweiten Raum stehen Faltwände, als kreisförmiger Sichtschutz angeordnet. Sie erinnern unwillkürlich an eine Pflegestation und verbergen vorerst mehr, als sie offenbaren. Eine Lücke in der Reihe der Paravents lockt ins Innere, wo ein feingliedriger Aderlassstuhl steht. Auf der Armlehne findet sich eine rot gefärbte Glasskulptur in Form eines überdimensionierten Blutgefäßes, die an eine Koralle erinnert – so auch der Name des Werkes: Flüssigkoralle. Die Zerbrechlichkeit der röhrenförmigen Struktur scheint unvermittelt zu entschleunigen: Um alles zu erfassen, schleicht man andächtig im Kreis um den Stuhl und die mundgeblasene Glasskulptur herum. Die erzeugte Intimität ist überwältigend allgegenwärtig. Umso mehr, als die antiquierte Vorstellung eines Aderlasses zur Heilung von Leiden jeglicher Art heute abwegig erscheint und doch über Jahrhunderte praktiziert wurde. Bei der Glasskulptur handelt es sich um ein äußerst seltenes eingeschmolzenes rotes sakrales Fensterglas, welches in seiner ursprünglichen Funktion das Drinnen vom Draußen und das Diesseits vom Jenseits trennen sollte.

Regal mit Medizinflaschen, 2017

Ein weiterer Raum enthüllt einen eigenartigen Medizinschrank, geformt aus grob verarbeitetem rosa Styropor und gefüllt mit abstrahierten weißen medizinischen Aufbewahrungsbehältern. Das Werk Regal mit Medizinflaschen erinnert an die nervöse Sehnsucht, „geheilt“ zu werden, oder an den Wunsch, hinauszuzögern, was am Ende des Lebens uns allen zusteht. Die Anordnung der Medizinflaschen wirkt, als habe jemand in Eile Heilung gesucht und unachtsam im Schrank gewühlt. Das Leben als ewige Pflegesituation ist keine Aspiration, wird jedoch immer häufiger zur Realität, denkt man an unsere andauernden Bemühungen, den unaufhaltsam alternden Körper so lange wie möglich am Leben zu erhalten. Leiden heißt auch, sich lebendig zu fühlen, versichert mir Ramírez-Figueroa und verweist auf die narrative Inszenierung des Fußes, der aus dem Medizinschrank heraustritt.

Die Installation zeugt von einer ehrlichen Empfindungswelt, die wiedergibt, was wir mit technischem und medizinischem Fortschrittsoptimismus hartnäckig zu ignorieren versuchen. Nämlich, dass wir Lebewesen, trotz aller Sehnsüchten, den Bedingungen der morbid nagenden Zeit unterworfen sind.

Comb Bound Sound, 2017

In einem weiteren Raum findet sich erneut eine intime, fast bühnenhafte Anordnung von Faltwänden, bezogen mit blau gefärbtem Stoff. Im Zentrum steht eine Venuskammschnecke (Murex pecten), ein äußerst fragiles Meereswesen, das der Künstler aus transparentem Glas produzieren ließ. Als Vorlage dienten illustrative Aquarellzeichnungen, welche wie so oft am Anfang seines Schaffensprozesses stehen. Das Werk trägt den Titel Comb Bound Sound. Aus dem Innenleben der Stachelschnecke dringt stumpf Musik. Wer genau hinhört, erkennt eine Fandango-Melodie, die das Stachelkleid leicht vibrieren lässt. Fandango bezeichnet einen spanischen Singtanz, der sich etymologisch auf Fandanguero zurückführen lässt, ein Wort für Sklaven, die heimlich Tänze aufführten und nächtlichen Tumult verursacht haben sollen. Ramírez-Figueroa wählte eine Interpretation des US-amerikanischen Cembalisten Scott Ross, der viel zu früh an den Folgen von Aids aus dem Leben geschieden ist – und eigene Sehnsüchte und Begierden bedeckt hielt, weshalb viele nie deutlich gegen außen erklangen.

Ramírez-Figueroas Werke schürfen allesamt in den tieferen Gesteinsschichten des Lebens und halten dort inne. Dass hier jemand von sich und seinem Leben spricht, ohne ein Wort darüber zu verlieren, ist auch der Ausstellung anzumerken.

Seine flüchtigen Traumwelten zeigen auf, wo wir die Schönheit vermuten, aber nicht sehen. Indem wir diese Schönheit suchen, werden wir mit dem Gefühl belohnt, sie gefunden zu haben – als würden wir der Schönheit für einen kurzen Augenblick in der Dunkelheit gegenüberstehen. Umgeben von Erinnerungen und Fantasien eines der eigenwilligsten Künstler der Gegenwart, der uns wie kein anderer lehrt, dass wir die Schönheit nicht sehen müssen, um zu wissen, dass sie unzerstörbar ist.

InformationInformation

The essay has been written by Sandino Scheidegger on the occasion of Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa’s solo exhibition Two Flamingos Copulating on a Tin Roof at the Museum Haus Esters in Krefeld. The exhibition was curated by Dorothee Mosters.

Download essay: English, German

Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa lives and works in Guatemala City, Guatemala, and Berlin, Germany. His work has been included in the 57th Venice Biennale (Italy), the 32nd Bienal de São Paulo (Brazil) and he had solo presentations and performances at the Tate (UK), Guggenheim (USA), Ultravioletta (Guatemala), KunstWerke (Germany), Nixon (Mexico City), Despacio (Costa Rica) or the CAPC musée d’art contemporain (France).